FRONTLINE

TRUTHS

By the Pacific Climate Warriors

Over thousands of years, Pacific islanders have moved in response to changing environmental, political or social conditions. Movement within and from the Pacific has been both sustaining and disruptive. It has enabled the cross-fertilisation of ideas, skills, knowledge and cultural practices, but it has also separated people for long periods from family, community and home. The climate crisis has brought about the need for a new wave of migration, one that is not being taken by choice.

We need to create a world where Pacific peoples have the right to stay on their land and the right to leave with dignity. In order to do that, we must be guided by the lived reality of Pacific peoples on the frontlines of climate-induced migration. We must honour their stories and demand that any framework, policy or agenda for our movement be informed by our truths.

The following are our truths as a people at the frontlines of climate change. These are our stories, bearing witness to the reality of climate mobility and the resilient spirits of our people.

CLIMATE MOBILITY

SAMOA

Every Samoan can recount a memory of a tropical cyclone. The swift organising to prepare homes and vulnerable community members for the battering to come. The mobilising of resources to move everyone to higher ground to escape the inevitable flooding. Now, the severity of these impacts has driven many from their homes, and with this relocation, comes a whole new storm of troubles.

Aniva Lokeni from Manono

Aniva speaks of sea-level rise in her homeland, one of Samoa’s smallest islands, Manono. Families have had to relocate due to the slow-onset impacts of climate change and this places a physical and mental strain the community, particularly the elderly.

Helen Schwalger from Lotopa

Helen speaks of the relocation happening in her village, Lotopa, due to massive floods and infrastructure damage, making her home unsafe to live in.

Litiana Elder from Moamoa

The floods in Litiana’s village created many problems for her growing up, but the relocation of her home has given her a sense of safety.

Republic of Marshall Islands

Jo-Jikum, a nonprofit based in the Marshall Islands focused on youth, climate change, and environmentalism, helps young people communicate their concerns about the climate crisis through activism. These are the stories of of Jo-Jikum youth coordinator, Jobod Silk, and Marshallese students who participate in a climate change art workshop.

Jobod Silk

Marshallese have always been a people of the sea, navigators sailing from one island to another, over the vast blue ocean. Always moving. However in 1954, displacement was introduced when the US military used our islands as a nuclear weapons testing ground.

Deceived and misinformed, the people of Enewetak and Bikini migrated to a land that was not theirs, giving up their homes “for the good of mankind”. The neighboring atolls of Rongelap and Utrik, were then contaminated by the radioactive fallout that was deliberately scattered by the winds. The people of those atolls, too, had to relocate.

Today, many of these people are unable to return home, as scientists proclaim the islands inhabitable. They have become nomads, wandering in foreign lands, lamenting over their loss.

Today, the threat of climate change puts us on the verge of displacement once again.

But this time we are putting our foot on the door. Never again do we want to be put in that position. We are adapting, we are mitigating, we are staying, “even if it means we are swimming in our own homes”.

Kiyoshi Takashi

Wherever we go, we as Marshallese would still follow our cultures. It doesn’t matter where we are – we would still follow our culture. Culture that you learn is a part of you – just like the organs inside of us. My art shows an astronaut performing a traditional fishing method. You can see that the planet is different from our planet, Earth. For his efforts of following the old ways, he caught a green alien like fish for food.

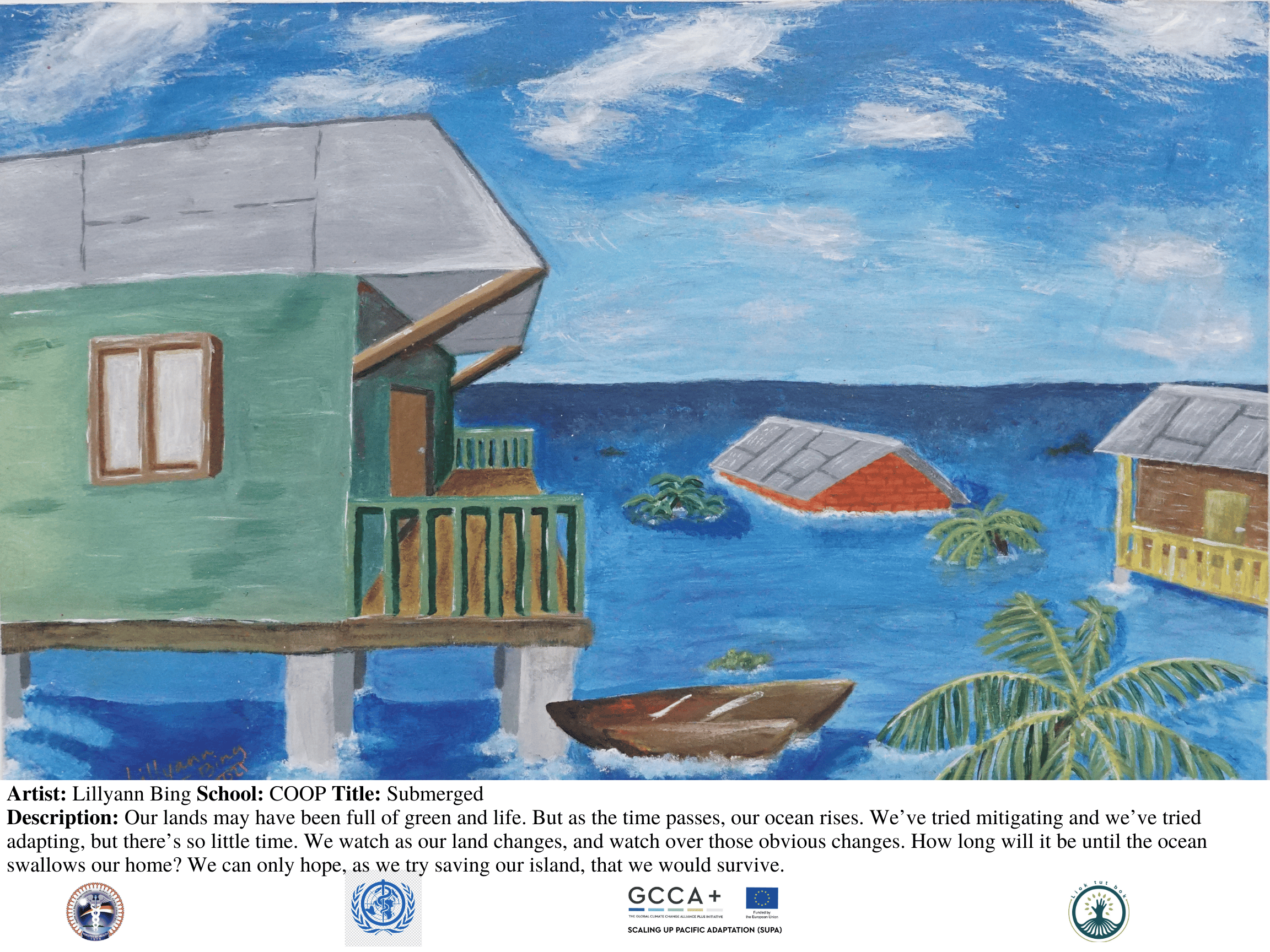

Lillyann Bing

Our lands may have been full of green and life. But as the time passes, our ocean rises. We’ve tried mitigating and we’ve tried adapting, but there’s so little time. We watch as our land changes, and watch over those obvious changes. How long will it be until the ocean swallows our home? We can only hope, as we try saving our island, that we would survive.

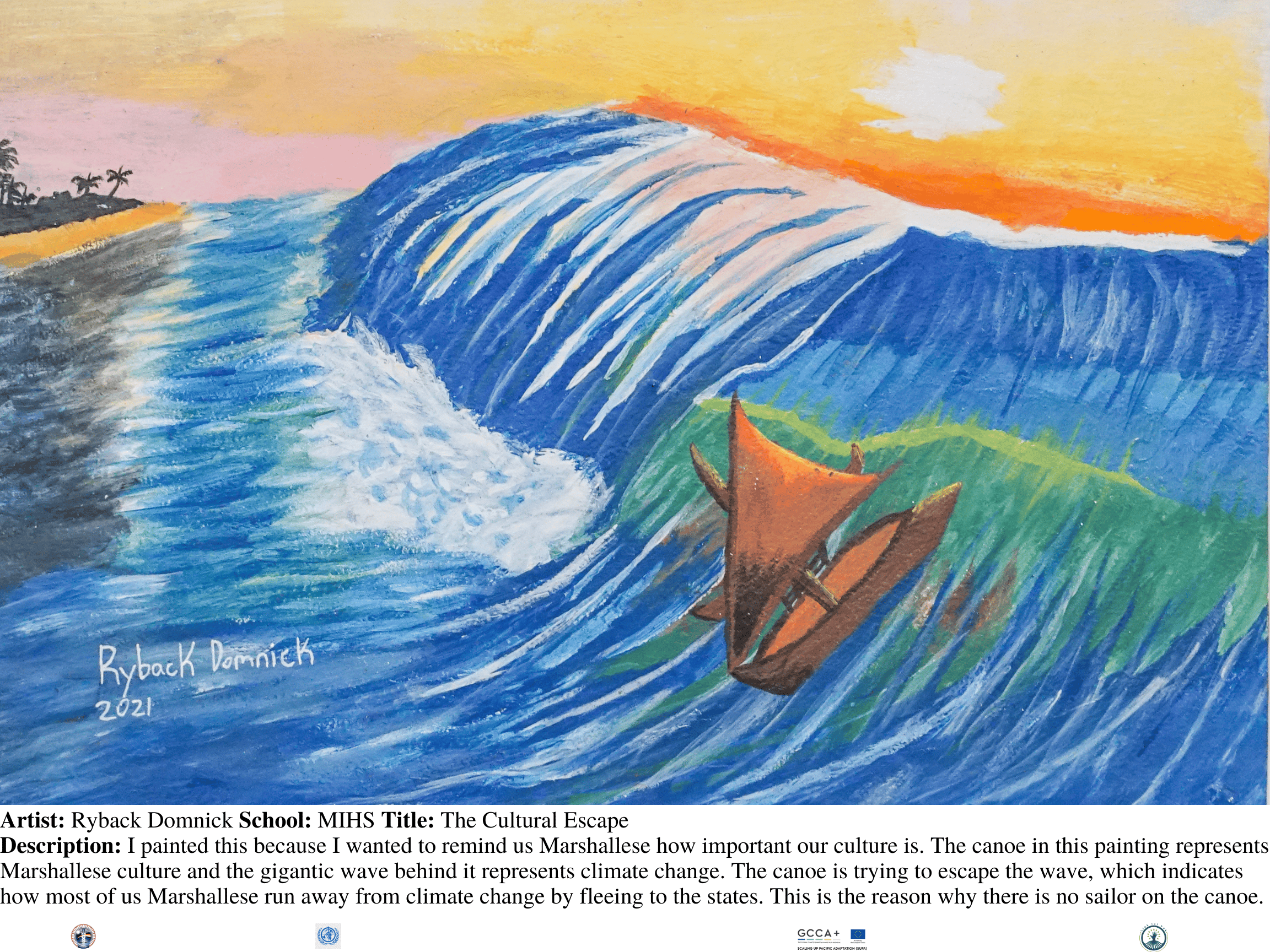

Ryback Domnick

I painted this because I wanted to remind us Marshallese of how important our culture is. The canoe in this painting represents Marshallese culture and the gigantic wave behind it represents climate change. The canoe is trying to escape the wave, which indicates how most of us Marshallese run away from climate change by fleeing to the States. This is the reason why there is no sailor on the canoe.

Fiji

Akuila Soconibalawa Tabakece

Akuila Soconibalawa Tabakece

I was at home in Cogea village in Fiji when Tropical Cyclone Yasa struck, and the 17th of December 2020 became the most frightening night of my entire life. The young men had prepared the village for cyclone winds and rain, but what we did not anticipate was the neighbouring Wainunu and Waininaro rivers breaking their banks. Throughout the day, I was part of a group of boys helping people prepare for the cyclone by pinning roofing iron to their windows, ensuring their houses were strongly braced to face the cyclone, moving boats and bilibili to dry land and moving people to our evacuation centre – the village church.

To our surprise, at 8pm, the two neighbouring rivers broke their banks, and flood waters began to rise. Our evacuation centre was at the level of rising waters, and as youth, it was our responsibility to move people from our village church to one of the houses built in an elevated area in our village, at the very height of the category 5 cyclone. We could only watch with horror from the houses we were sheltering in that night as we saw houses moved from their foundation and washed away by the strong currents of the flooded rivers. On the morning of December 18 2020, we watched our homeland with a heavy heart, knowing that the pieces of land we call home were no more.

Samuela Tabakece

Samuela Tabakece

Cogea village in the district of Wainunu, Bua was severely affected by Tropical Cyclone Yasa on December 17, 2020. Up to eighty percent of the village was inundated and 18 of the 40 houses were destroyed.

We were identified as a community prioritised to be relocated to a safe site. A site assessment of our village demonstrated that its current location, on a floodplain flanked by the Wainunu river to the west and Naro creek to the east, was no longer safe for dwelling.

Two potential sites were identified for our village, namely Naro and Navudi. After consideration of road, water, and other basic neccesity access, Naro was selected. Its subsurface condition was also considered the most suitable site for our relocation. A mataqali (clan or landowning unit), Nalomate, from the chiefly village of Daria (where I have maternal ties to), gave their approval and the Veitarogi Vanua under the iTaukei Affairs officiated in the land handover process.

But nothing has since materialised. We are still living in tents and some villagers have resorted to just rebuilding their homes on their own mataqali land. Building materials have been delivered but we cannot begin to build our homes on the new site until the cadastral survey is done, which is what our community has been waiting so long for. It has been 2 years since Cyclone Yasa and we are not safe here. There is confusion and despair among the people, and my commitment to my village is to make sure that the world hears our story.

Niue

Maryanne Talagi

In 2004, Cyclone Heta devastated the islands of Niue, Tonga and Samoa. Today, Maryanne Talagi from Makefu in Niue speaks about the experience of relocating due to the effects of Heta, and the seemingly constant journey inland as climate impacts threaten coastlines.

Tuvalu

Luamano Lusama Lalaia

Luamano Lusama Lalaia is a Tuvaluan woman who has lived in both Tuvalu and Fiji. Upon visiting Kioa, an island in Fiji populated by the relocated community of Vaitupu, Tuvalu, she discovered many missing links. The story of Tuvalu and Kioa is a story of Tuvaluans thriving in a new home, but also a lesson in the importance of keeping families connected in the face of migration.

Rabi

The history of the Banaba people is a lesson to the world. We were forcibly relocated, by Australian, British and New Zealand governments, from our island home in modern-day Kiribati to an island in Fiji. Our relocation was a direct result of extractive industry and global trade. We bear testimony to the human cost and trauma borne by a community. We are what non-economic loss and damage look like. We do not want any other community to go through what we experienced.

– Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration, 2022

Benieri Nakarua

We lost a lot of our culture and our traditions during the migration. Banaba culture is linked to the land and to the environment. Because I grew up in Rabi, I have a strong connection to the land of Rabi and that shapes my culture, but our elders still yearn for home and theirs is a culture different from mine.

On December 15th every year, the anniversary of the migration, our elders would tell us stories of Ocean Island (Banaba) and hearing these stories year after year, the youth now want to take a trip to our homeland. But it is not easy and the journey is long.

This could become the same struggle for climate change migration, and we hope that the future can learn from us. If communities need to relocate in the future, I ask you to have strong documentation of your culture. Document your culture, your stories and every part of the movement from your homeland. We were forced to move so there was not enough documentation, and because of that, there is sometimes conflict. Families will argue about whose role it is to garland a guest, clans will argue about the details of our cultural sports. These are the effects of forced relocation. If I was raised in Banaba, I would know these things but because I was not, I can only rely on what stories and information survives in Rabi.

Itinterunga Rae Bainteiti

The forced migration of the people of Banaba Island in Kiribati happened in many waves. After Australia and New Zealand discovered phosphate on the island, Banabans were dispersed to the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Tarawa and some were sent to the island of Rabi in Fiji.

When my people settled on Rabi 77 years ago, they were promised homes. When they arrived, they lived in tents. They were given two weeks worth of rations and after that, had to scour this new and foreign land for food. We lost elders and children to illness because there were no hospitals, no treated water and no sanitation.

Photo: Rabi Council

Still, we learnt to adapt and thrive in our new home and the youth proudly call ourselves Fijians. But in Fiji, we are still Rabians – we are still Banabans. It wasn’t until high school that I realized we were different to native Fijians and I traveled back to Kiribati to learn more. Yet, when I arrived in Kiribati, I faced an entirely new identity crisis. People told us we were Fijians. “He’s Rabian, he’s Fijian. Tell him to go back to Fiji and find his own scholarships and his own jobs.” Banaban youth cannot access our home island of Banaba unless we can prove our ancestry, and that process is messy in itself.

Photo: Rabi Council

After my teenage years in Kiribati, I returned to Rabi inspired to change things for my people and ensure communities that may have to relocate in the future do not suffer as we did.

Climate change is forcing another wave of migration and we know what it feels like to be relocated because of extractive industries and environmental degradation. We know how important it is for there to be plans in place to make sure that, should the worst case scenario happen and people need to relocate, they can do so with dignity.

We are a generation that is so angry because the process of our migration did not work for our people. But we do not dwell on what has happened in the past, we want to move forward, using these lessons learnt so that it can help other migrants that will have to cross borders to survive. We want to ensure that they are guaranteed basic human rights. The right to life, the right to access their homeland and the right to be their authentic selves wherever they want to call home.

FRONTLINE

TRUTHS

CLIMATE IMPACTS

As young Pacific Islanders working in the climate movement, our role must be to to shift this single story that paints us as victims of climate change, to one that reflects our multiple truths as Pacific Islanders, living with climate impacts, but thriving nonetheless.

As a people, we need to retell our stories. We need to shed light on our multiple truths and record this part of our history, so the next generation can learn from our stories. Not just for the sake of Pacific Islanders in the climate discourse, but for Pacific Islanders in general.

Last year, the Pacific Climate Warriors blockaded the largest coal port in the world to send a direct message to the fossil fuel industry. This year, we will send a message to those investing in the climate crisis.

The following are our truths as a people at the frontlines of climate change. These are our stories of how we are bearing witness to climate impacts as well as holding strong to the resilient spirits of our people.

Frontline Truths: Kiribati

The first island to tell their stories is Kiribati, earlier this year Kiribati was hit with King Tides that destroyed nearly everything in its path.

While king tides occur naturally, we know that climate change played a hand in making the king tides more extreme. It’s given us a sobering indication of just how damaging any sea-level rise from here on in will be for Kiribati. Small amounts of sea level rise are causing disproportionately large amounts of damage

Photos and interviews by 350 Pacific Communications Coordinator Fenton Lutunatabua

Frontline Truths: Papua New Guinea

The next island to share their stories is Papua New Guinea. Again, we would like to reiterate, that while king tides aren’t a direct result of climate change, it does make them more extreme.

A team from 350 Papua New Guinea recently travelled to Buka to collect stories from the people of the Carteret Islands- some of the world’s first climate change refugees. The team, headed by Arianne Kassman, 350 PNG Coordinator, collected first hand accounts of climate change realities in the Carterets.

Frontline Truths: Vanuatu

The next island to tell their stories is Vanuatu. Earlier this year Vanuatu was hit by Tropical Cyclone Pam– the worst natural disaster in the history of Vanuatu, and the strongest storm ever in the South Pacific. We know that climate change plays a hand in making these cyclones more extreme.

Photos and interviews by 350 Vanuatu Coordinator Isso Nihmei

Frontline Truths: Solomon Islands

Next we travel to the Malaita Province, where 350 Solomon Islands Coordinator, Starling Konainao speaks with elders in Auki Harbor about climate impacts in their community.

I am Starling Konanaio, and I come from Lilisiana and Ambu, both communities are located on each side of the Auki Harbor. The Malaita Provincial capital is located at the centre. As coastal communities, we rely on the sea for both food and economic activities.

Frontline Truths: Fiji

Next, we travel to the Fiji islands where George Nacewa and the 350 Fiji team had travelled for roughly 12 hours to get to Vunisavisavi, a small village on the second major island in the Fiji group, Vanua Levu. Vunisavisavi was identified by the iTaukei Affairs Board (the administrative arm of the Government that looks after indigenous people of Fiji), as a community that may need to relocate due to the impacts of climate change. George spoke with a few villagers to understand their realities with climate impacts.

Frontline Truths: Tokelau

Next we travel to Tokelau, where Climate Warrior Litia Maiava shares her truths as a Pacific Islander living with the impacts of climate change.

Frontline Truths: Marshall Islands

by Niten Anni from the Marshall Islands

My home is made up of a few small and low-lying atoll islands. There are about 70,000 Marshallese people that make up our population. A majority of them live on Majuro, which is the capital, and Kwajalein, which is the largest atoll in the world.

Today, our islands, much like many other atoll islands, are in great danger because of climate change. King tides, which are exacerbated by climate change, damage many of our homes and destroy many of our beaches making them smaller and smaller.

Years ago, our land was wider and larger. Now with climate change our land is getting smaller and smaller due to the rise in sea level.I remember when I was a child, my friends and I use to play on the beach, but now it’s gone. Our beach is underwater and I can’t imagine what it will be like in the next twenty years if we do not fight against climate change. Our homes may go underwater, we may lose everything!

Years ago, our land was wider and larger. Now with climate change our land is getting smaller and smaller due to the rise in sea level.I remember when I was a child, my friends and I use to play on the beach, but now it’s gone. Our beach is underwater and I can’t imagine what it will be like in the next twenty years if we do not fight against climate change. Our homes may go underwater, we may lose everything!

My father built my family three homes to live in. Unfortunately, these homes were destroyed by Cyclones Val and Olaf in 1991 and Cyclone Percy in 2004. This wasn’t just unique to my family, many other homes close to the sea were destroyed. People have told us to move because they believe Tokelau will disappear in the next 20 to 50 years. I cannot, I will not, I have to stand my ground as a Tokelau Climate Warrior and defend my islands. This is my responsibility and duty to protect my land from the threat of climate change.

My father built my family three homes to live in. Unfortunately, these homes were destroyed by Cyclones Val and Olaf in 1991 and Cyclone Percy in 2004. This wasn’t just unique to my family, many other homes close to the sea were destroyed. People have told us to move because they believe Tokelau will disappear in the next 20 to 50 years. I cannot, I will not, I have to stand my ground as a Tokelau Climate Warrior and defend my islands. This is my responsibility and duty to protect my land from the threat of climate change.